Posted on July 24, 2025

Alma Mater / OSR Mash-Up

I recently ran a one-shot games day for a group of friends I rarely get to game with in person anymore. After a friend’s initial suggestion I’ve been thinking a lot about a campaign premise not entirely dissimilar to the original Dungeons & Dragons cartoon series, in which a group of high-school students enter into the fantasy world of D&D. I decided to use the one-shot games day to play with some ideas for such a campaign, and since I am a fan of all things old-school, I was tempted to use perhaps the original RPG to be “cancelled”: Alma Mater, mashed up with my own OSR game Mailed Fist. While I don’t think I’ll use Alma Mater for an actual campaign built around this premise, as a one-shot games day catching up with old friends, incorporating Alma Mater added a little bit of “spice” to make things interesting.

What’s Alma Mater?

If you’ve persisted this far and have no idea what this Alma Mater game I’m talking about is, here are some helpful links to find out:

- RPG Geek: Alma Mater

- Grognardia: Retrospective: Alma Mater

- Immortals Inc YouTube Channel: Possibly the WORST RPG EVER Created?

That should give you a good enough idea!

Character Creation

Alma Mater has players roll 7 ability scores, each on 1d10. There are eligibility thresholds based on these ability scores for the character classes Average, Brain, Cheerleader, Criminal, Jock, Tough and Loser. These character classes are immediately evocative of 1980s high school archetypes. Before entering the fantasy world, the player characters are simple high school students, with stats and skills (and game world rules) all per the Alma Mater game. When they cross over to the fantasy world, then the characters become equivalent OSR characters.

Alma Mater to OSR Attributes

| Alma Mater | OSR |

| Strength (ST) | Strength (STR) |

| Coordination (CO) | Dexterity (DEX) |

| Appearance (APP) | Contributes to Charisma (CHA) |

| Intelligence (INT) | Intelligence (INT) |

| Learning Drive (LD) | Contributes to Wisdom (WIS) |

| Courage (CR) | Contributes to Charisma (CHA) |

| Willpower (WP) | Contributes to Wisdom (WIS) |

| Constitution (CON) (Derived Attribute) | Constitution (CON) |

Since Alma Mater attributes are on 1 to 10 scale, rolled on 1d10, I propose converting them to OSR based on score distribution vs a standard 3d6 curve (see the table below to assist). The exceptions will be CHA, WIS, and CON, for which an interim score will be calculated which will then be converted to an OSR score via the look-up table. The interim scores are calculated thus (round all fractions to the nearest whole number, 0.5 rounds up):

- Interim Score for CHA = ( APP + APP + CR ) / 3

- Interim Score for WIS = ( WP + LD ) / 2

- Interim Score for CON = Alma Mater CON / 2

Score conversion is then done using the following table:

| Alma Mater Score | OSR Score | Additional Step |

| 1 | 3 to 6 | Roll 1d6, 1: 3, 2: 4, 3: 5, 4-6: 6 |

| 2 | 7 | |

| 3 | 8 | |

| 4 | 9 | |

| 5 | 10 | |

| 6 | 11 | |

| 7 | 12 | |

| 8 | 13 | |

| 9 | 14 to 15 | Roll 1d6, 1-3: 14, 4-6: 15 |

| 10 | 16 to 18 | Roll 1d6, 1-2: 16, 3-4: 17, 5-6: 18 |

After converting the ability scores from Alma Mater to OSR ability scores, the appropriate OSR character classes will probably suggest themselves easily enough. In my Mailed Fist conversion, the following class conversions were used:

| Mailed Fist Character Class | Alma Mater Character Class |

| Cleric | Average (I had a couple of “very religious” pre-gens who became clerics in the fantasy world – their Alma Mater class probably wasn’t very important) |

| Fighter | Jock, Tough |

| Magic-User | Brain |

| Specialist | Everyone else! Appropriate skill selections from Mailed Fist were used to create “custom classes” like Acrobat, Bard, Thief, etc based on the Alma Mater character |

Skill Conversion

Most Alma Mater skills will not come up much during play in the OSR style fantasy world, and so we are looking for “near enough is good enough” conversion. In Mailed Fist or Swords & Wizardry you could use the skill level as a (positive) modifier on a saving throw used for task resolution, and apply the Alma Mater skills in only the most general way. Some Alma Mater skills provide for modifiers to different types of rolls (e.g. seduction) which can be applied “as is” to a saving throw or task resolution roll for a similar task in the fantasy world, but for other Alma Mater skills, the Alma Mater rules could be used entirely “as is” even in the fantasy world with appropriate discretion by the Referee. It’s probably not a good idea to convert combat skills from Alma Mater to the OSR fantasy world as this will probably lead to “overpowered” OSR characters.

Posted on October 31, 2024

Arduin, Wonderful Arduin!

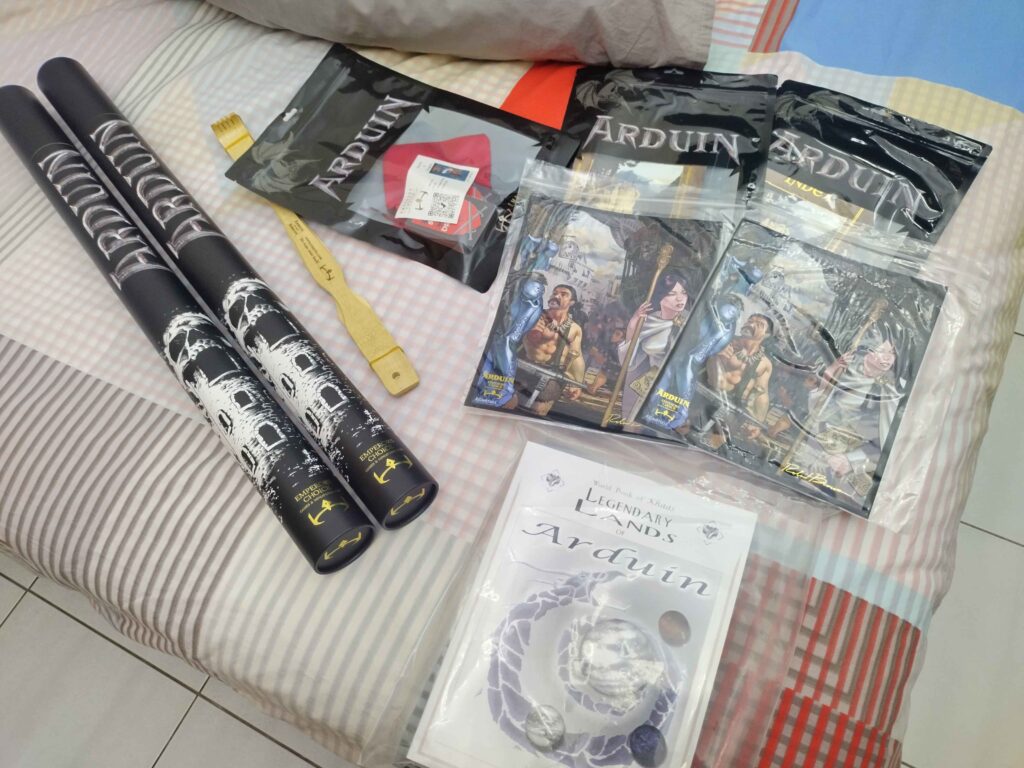

After my first shipment was lost by the carrier on my end, the wonderful David and George at Emperor’s Choice shipped me a replacement, full of extra goodies. I cannot express my glee!

During my period of inactivity on this blog, I stumbled onto Arduin (many OSR bloggers and podcasters stumbled across it around the same time so I probably have someone else to thank) and quickly fell in love with its idiosyncratic, high energy, kitchen-sink fantasy style – not to mention the Arduin Trilogy‘s pages and pages of glorious tables. I was therefore excited when Emperor’s Choice launched a Kickstarter this Summer, and even more excited when they very quickly fulfilled the Kickstarter with a set of stunning maps, art carts, and index box. They even threw in two (!!!) official Arduin back scratchers!

I am very much looking forward to Arduin Bloody Arduin, the new OSR edition of the game Emperor’s Choice has been working on. In the meantime, I will continue to entertain myself with these goodies and with my copy of Arduin Trilogy (available as a PDF on DriveThruRPG via this affiliate link, or in print from Emperor’s Choice). I’ll be sure to post again about Arduin in the future.

Posted on October 30, 2024

Exorcism

Most (but not all) of the Cleric NPCs in my Lamentations of the Flame Princess campaigns have been Christian clergy. Since my campaigns were mostly set in Early Modern Europe, that seemed to be an appropriate decision. Player characters Clerics have been more varied in their religious beliefs, but then, player characters are always exceptional in some way. Just as there were many infamous witch hunts in the 17th century, there were also many documented cases of (apparent) demonic possession. Often these were integral to the matters under investigation in the various witch hunts, of course. The Christian Rite of Exorcism was employed in such cases to expel demons from their unfortunate vessels, and frankly not only was it more historically and theologically correct, it also seemed more useful for Clerics in most circumstances than Turn Undead!

Here is a spell for Clerics in Basic D&D retroclones and derivatives, like Lamentations of the Flame Princess, intended to let them practice the Rite of Exorcism. I offer the spell as open game content if anybody is still game to use the OGL!

Exorcise

Cleric Level 1

Duration: Instantaneous

Range: Touch

This spell can drive a demon out of the victim of a demonic possession, or assist the caster in the interrogation of a demon which has possessed the mortal target of this spell. It cannot be used to banish a demon which has physically manifested outside of the body of a mortal host (for which purpose the spell Dispel Evil is recommended). The caster rolls 1d20 and adds their level, and either their Wisdom or Charisma bonus (whichever is higher). By placing holy relics on the head of the possessed person, the caster may obtain a further bonus of +1 to +3 depending on the holiness of the relics. The demon rolls 1d20 and adds their number of Hit Dice (the Hit Dice of the demon’s physical manifestation, not of their mortal host). If the caster does not call the demon out by name (if, for example, they do not know the demon’s name), then the demon adds +1d6 to their score. The Referee should roll the demon’s roll in secret. The caster must beat the demon’s score to cast the demon out. The degree of success or failure influences what happens next:

- Caster succeeds by 10 or more: The demon is driven out, and can never return to the same host again. If there is another demon present in the host whose presence is unknown to the caster, it will make itself known and reveal its name.

- Caster succeeds by 5 to 9: The demon is driven out, and cannot return to the same host for at least 3d12 days. If there is another demon present in the host whose presence is unknown to the caster, it will make itself known and reveal its name.

- Caster succeeds by 1 to 4: The demon is driven out of the host, and cannot return to the same host for at least 3d12 days.

- Draw: The demon appears to be driven out of the host, but is still present inside. It cannot resume control over the host for at least 3d12 hours, however.

- Caster fails by 1 to 4: The demon remains. If the mortal host is physically restrained, then the caster can ask the demon 1d4 questions, and the demon must answer truthfully to the best of its knowledge. The demon is not compelled to be helpful, however, and if the caster asks ambiguous questions, the demon is free to give ambiguous (though technically truthful) answers. If the demon does not know the answer to a question, the question is lost. If the mortal host is not restrained, then the demon will force the host to attack the caster.

- Caster fails by 5 to 9: The demon remains. If the mortal host is not restrained, then the demon will force the host to attack the caster. If the mortal host is restrained, the demon will attempt to free the host, lending them superhuman strength (+1d10 Strength) for 1d6 rounds to help break free.

- Caster fails by 10 or more: The caster must make a saving throw against Magic. If they fail, then the demon leaves its current host, and takes possession of the caster instead. If they succeed, then the demon attacks and/or attempts to break free, as above.

Posted on August 9, 2024

Review: Wight-Box

In recent years, while not posting here, I have been increasingly interested in OD&D and various retroclones. Many of these retroclones will be very well known to anybody likely to read this blog, and I do have a good many of them. There have been a couple which have come out recently which have particularly excited me, however, so much so that I was motivated to get back to posting here with a review. Wight-Box: Original Medieval Fantasy Adventure Campaigns is a retroclone by The Basic Expert, available both as pay-what-you-want as a PDF and in soft and hardcover in print from DriveThruRPG (affiliate links). I purchased my copy in softcover print.

I was drawn to Wight-Box because it advertises that it is based on Chainmail and the original 3 little brown books. I’m particularly interested in integrating Chainmail with OD&D, and I spent a good amount of time during the pandemic and subsequently working on my own “alternate evolution” of D&D, Mailed Fist, based on the combat system evolving more from Chainmail and less from the “alternative combat system” presented in OD&D Book I (i.e. the d20-based system). Wight-Box goes a different direction, sticking with the d20 mechanic, but adapting Chainmail‘s man-to-man combat system to the familiar d20, and doing a lot of other interesting work besides with a novel, well-organized presentation of OD&D. What emerges is a game which has both simple and familiar mechanics, but is also satisfyingly “crunchy” thanks to the extra bits from Chainmail which many retroclones forego.

The game has the same three character classes (Cleric, Fighting-Man, and Magic-User) as OD&D. Perhaps the name “Fighting-Man” is retained out of reverence for the original? All three classes are presented with their Chainmail Fighting Capability as they were presented in OD&D Book I (e.g. 2 Men, or Hero +1). In the combat rules, Wight-Box explains that Fighting Capability is used when fighting non-heroic level opponents (e.g. monsters with less than 4 hit die), when the attacker uses their Fighting Capability (or a Monster their HD) to determine how many attacks they can make against such opponents. These attacks are made at level 1 (i.e. without a higher attack bonus unless provided for by their Fighting Capability). When facing opponents of higher level, a single attack is made at the attacker’s character level per the attack matrices in the “usual” way familiar to the “alternative combat system”. This is one way Chainmail concepts are married with the alternative combat system.

Wight-Box also adapts Chainmail elements to the d20-based combat system by incorporating weapon class and different weapons being better or worse at attacking opponents with different armour. Some of this appears in other retroclones, and modifying the “to hit roll” required to hit a particular armour class based on the weapon being used made it into AD&D, although I’ve never played in a group which used the weapon type and armour class adjustments from the AD&D PHB. Weapon class also influences the ability to parry an opponent’s blow, and who attacks first. In this respect, Wight-Box is similar to my own game, although I think Wight-Box‘s presentation of the effects of weapon class is clearer than my own (at least in the current playtest version of Mailed Fist – maybe I can learn from that for the next release).

Beyond these mechanical “marriages” of Chainmail with the d20-based “alternative combat system”, Wight-Box also presents clear presentations of the different “subsystems” of OD&D and Chainmail, including air combat, naval combat, jousting (from Chainmail), and domain rules. In addition to this, there are appendices including novel subsystems/rules: dungeon generation, hex generation, oracles, NPC generation, room content generations, a thief class, and an adaptation of pole-arm rules from the Strategic Review. Collectively, it’s accessible, well-organized, and appealingly presented as a compact but “crunchy” ruleset.

Wight-Box is a well-put together retroclone of OD&D as presented in the 3LBBs and Chainmail. It’s based on the 5.1 SRD, not on Swords & Wizardry or Delving Deeper or another popular OD&D clone, and if you are looking for “yet another retroclone” of OD&D with some thoughtful incorporation of Chainmail concepts, Wight-Box is a worthy purchase.

Posted on October 26, 2020

Colony of Death

Colony of Death: Weird Fantasy Roleplaying in 17th Century Maryland is a third-party adventure module for Lamentations of the Flame Princess by Mark Hess. It is available in print via Lulu and via PDF from DriveThruRPG (affiliate link). This review is based on a reading of the print version, not on actual play. The author, Mark Hess, has released two other third-party products for Lamentations of the Flame Princess, but this is the first one available in print.

Colony of Death is a 58 page softcover adventure setting, including a high level summary of the English colony of Maryland in 1650, a colour hex map of the setting, a bestiary, random encounter tables, four brief adventures, and several other sections to bring some 17th century colonial flavour to your table, including New World Diseases and rules for growing tobacco in Maryland colony. There’s a lot of value packed into those 58 pages at a very reasonable price – $1.14 for the PDF and $4.99 for the printed book! The module would be terrific value at three times the price.

I have been drawn to the idea of the New World (or a fantasy analogue for it) for my next Lamentations of the Flame Princess campaign for some time. You have wilderness exploration and relative isolation – both useful breeding grounds for horror. The existence of early European colonies in America was precarious – and that’s before you add any weird fantasy or horror complications. Colony of Death does a good job of giving us a sense of this historical precariousness with brief descriptions of the history of the colony and its people. The early religious tolerance between Catholics and Protestants gives way to the violence of the Plundering Times, for example, during which the English Civil War visits Maryland. The disease rules are suitably gritty and nasty, and establish deadly illness as an ever present and omnipresent fact of life in the colony (an historical state which somehow feels less distant in 2020 than it felt in 2019). In a short space, Hess paints an evocative picture of early colonial Maryland as an adventuring locale.

The bestiary is a combination of natural wildlife, supernatural creatures, and potential human foes. There’s 22 entries and random encounter tables for every type of hex in the Maryland map included in the module. The bestiary is not illustrated – some entries have a brief description text before the equally brief LotFP stat block, others are most self-explanatory and jump straight into the stat block. It’s a no-nonsense, working bestiary which will keep the player characters on their toes as they move about the colony. Like most LotFP products Colony of Death seems aimed at low-level characters so the encounters are mostly lower-level creatures, although there are a couple of 7 hit dice creatures too. It would be better with some artwork, but the bestiary is undeniably useful.

The adventures are a nice mixture of “mundane” and supernatural horror. They’re all sufficiently different from each other both to provide your campaign with some variety and to get you to think about the right mix of adventures for your own game. Any historical or pseudo-historical setting can only absorb so much “weird” before the historical aspects are so eclipsed by the weird ones that the setting no longer feels grounded and real – which in turn makes the weird fantasy elements feel less special. It’s important to get a mixture of mundane and supernatural adventures in your campaign in order to make sure the “weird” keeps feeling “weird”. I think this is the motivation for some recent official Lamentations of the Flame Princess releases such as No Rest for the Wicked and The Punchline. It is nice to see a mix of adventure types in a third-party product.

Colony of Death is 58 pages of gameable early colonial era weird fantasy roleplaying content with zero waste, and represents fantastic value in both formats. I highly recommend it. My only minor quibble is that the physical book I bought from US Lulu (it only seems to be available from the US at the moment) is printed in 6×9 inch format, which is slightly taller (just over 1cm) than the A5 size preferred by Lamentations of the Flame Princess. But that’s really nothing. This is a value-packed module, one of the best third-party publications for Lamentations of the Flame Princess I have purchased. If you want to run an OSR game in early colonial America, buy this book, you will not regret it.

Posted on July 26, 2020

Adventure Anthology: Blood

Adventure Anthology: Blood is the last of the planned three volumes of previously independently published LotFP features. The Adventure Anthology series has included Fire, Death, and Blood. Blood was recently released in print and PDF, and my print version has not yet arrived, so I am basing this review on the PDF. Blood is available from the LotFP webstore (EU store and US store) and in PDF only from DriveThruRPG (affiliate link).

Whereas the previous Adventure Anthology volumes reprinted adventures from the period after LotFP had found its feet as a publisher, which were already beautifully illustrated and laid-out, Adventure Anthology: Blood reprints some of the publisher’s earliest modules, and has therefore been given all new artwork and layout. This means that the PDF version of Blood is a PDF of the newly laid out and illustrated versions of the originals, not a ZIP file of the PDFs of the original adventures as was the case for Fire and Death. This makes Blood worthy of purchase even for those who own the originals, and even in PDF format, and appears to be why it was released on DriveThruRPG whereas the others were not. The artwork is by the talented author, artist, designer (and soon to be nude portraitist) Kelvin Green and the layout is by Alex Mayo. Both are mainstays of LotFP and their work updates the look of these adventures to be consistent with the high standards expected of the publisher in 2020.

The adventures in Blood are quite different from the “normal” LotFP fare from the era of the Rules & Magic book onwards. As James Raggi (who wrote all of the adventures in this volume) says in the foreword, these adventures are from “back in the day when I was still trying to fuse traditional heroic fantasy with my nascent understanding of the Weird.” This is actually a fondly remembered period in LotFP‘s history with many OSR Grognards found online, who complain that Raggi’s later works are “negadungeons” or less obliquely and more crassly, “party fucks”. While I don’t really agree with this assessment of the later LotFP titles, it does mean that this may be the first LotFP product in some time which may appeal to this “traditionalist” wing of the OSR, if they are willing to give a new title from LotFP a second look. This also means that these adventures are, on the whole, easier to adapt to a “standard” D&D campaign than most LotFP modules. It could even serve as a “gateway” book to gift a 5e DM looking for something different to do with their next game.

The first adventure in Blood is The Grinding Gear. Although I own the PDF of the original, I’ve never run this adventure. The premise is that an innkeeper with good cause to hate adventurers had his own tomb constructed as an adventurer-trap dungeon as revenge on adventurers as a social class as a cruel practical joke. It’s a fun, tongue in cheek premise. At first the adventurers will find an abandoned inn, but as they blunder through it, they will find the entry to the dungeon and there the real fun begins. The dungeon is initially surprisingly conventional (remember: this Raggi’s early work before all the elements of the current LotFP formula had come together), with progressively more devious traps and puzzles, especially once the players reach the second level. If the players do “beat” the dungeon and get the final treasure, they will have earned themselves a recurring opponent who “will test them again” – more like a determined prankster than a truly malevolent villain. I can imagine that players will feel pushed very hard by the traps and puzzles in the second level of the dungeon, and will indeed start to feel like the dungeon’s designer has tortured them for his own amusement. It’s not exactly eldritch horror, but it is a lot of fun and I think between the details of the dungeon’s designer and the types of traps and clues left in the dungeon, the tone is perfect, albeit quite different from newer LotFP adventures.

The second adventure in Blood is Weird New World. I’ve nearly used this module as the basis for a campaign twice, and each time reverted to the English Civil War because the players wanted to stay there. Weird New World is a sandbox inspired by the search for the Northwest Passage (but not actually based on the geography of the real world). LotFP had not definitively settled on Earth in the Early Modern period as its default setting when this adventure was originally published – in fact, the Grindhouse Referee’s Guide actively advises against using the real world as a setting – but it would be easy enough to imagine that this giant hexcrawl could take place in our own world, as a conceit to the idea that the area being explored really was unknown to those exploring it and that almost anything could be encountered up there in the icy northern waters. There’s a good mix between natural phenomena and beasts and fantasy creatures (elves most notably). Weird New World also features the “Eskuit”, a native people of many tribes, generally with a bad impression of elves (understandable given the nasty elves found in this module). In the political climate of 2020, I am genuinely not sure how the Eskuit will be perceived – to my reading, they are presented as a fairly obvious stand-in for the Inuit and nothing seems to be intentionally offensive or insensitive in their portrayal but I am not the one who gets to make that call. Exploration and colonial exploitation were themes of adventuring in the real-life 17th Century which seem like they are important and worthy of inclusion in any game using this historical setting however broadly. Weird New World may not be our “New World” but it seems far more appropriate to me that it has native peoples of its own just as the real “New World” which was explored and exploited by the European powers in this period did. Weird New World is an interesting sandbox for an exploration/wilderness survival horror campaign, and it’s one I keep coming back with the intent to use myself. Maybe someday!

The third adventure in the Blood volume is No Dignity in Death. This module is an extremely early one in LotFP history and until now I’ve only had it in A4-sized PDF, so the format update to be consistent with the rest of the LotFP line is extremely welcome. This adventure features “gypsies”, with Raggi’s heavy disclaimer that the portrayal is intentionally inaccurate and explanation of the prejudice against these people which he observed when he first moved to Finland and how surprising it was and how this influenced his decision to make the victims in this adventure gypsies to see what his players would do with the setup. Dealing with the prejudices of your players towards the ethnic group of the people they are supposed to be helping in an adventure may be a lot heavier than you might prefer in your elfgame! Much as the presence of the Eskuit in Weird New World may offend some, so may the presence of gypsies in No Dignity in Death – and it is not my place to declare these portrayals as “fine”, but at least in this adventure Raggi has made a conscious decision to make the victims who need the party’s assistance an exaggerated stereotype of an ethic group which is the victim of discrimination even in “enlightened” 2020 Europe. No Dignity in Death is set in Pembrooktonshire, a fictitious community which would be easily enough incorporated into a typical fantasy campaign setting or into Early Modern Europe (although it will require significant modification to really strike an historical feel, which may end up ruining the vibe).

There are really three different “adventures” presented in No Dignity in Death all presented in and around Pembrooktonshire, which is enormously detailed, with about one hundred pages of this volume given over to describing the community and its inhabitants in the People of Pembrooktonshire chapter. There’s a huge amount of material to mine here and Pembrooktonshire could easily become the base of your campaign. The key thing to know is that Pembrooktonshire is isolated and insular and has a strong sense of character which will come across in play. The players will realise that this is a distinct community with its own traditions and local culture. It’s also a profoundly weird place, albeit a very different kind of weird from the weird found in most of the more modern Lamentations of the Flame Princess line – it’s more surreal than horror, in my assessment. The three adventures in No Dignity in Death can be summarized as: a murder mystery, a deeply messed up local competition/human sacrifice, and a location-based adventure in the mountains. With all the details from the People of Pembrooktonshire chapter, these adventures have the potential to come to life, especially if you and your players like to get into character and roleplay social interactions.

The final adventure in Blood is Hammers of the God. In another departure from “modern” LotFP, which eschews demihumans, this adventure is based around dwarfs. This has advantages and disadvantages. How much do you like dwarfs? Depending on how much “dwarf lore” is established in your campaign setting, you may find that the adventure isn’t usable because dwarfs as they appear here are not the dwarfs of your campaign setting. If your dwarf lore is a bit more malleable, however, then this adventure is a world-building romp. Despite this being the most “traditional fantasy” adventure in the module, the weird horror flavour of Lamentations of the Flame Princess starts to come through with wormholes, aliens, and tentacles on random tables and in room descriptions. The appendices of this adventure have some useful tables, but one of them is very strangely laid out – “Appendix II: Book Descriptions” is a d100 table which spans many pages, but strangely, the reverse pages are blank. There doesn’t seem to be any reason for this layout decision – I am just reviewing the PDF though since the book has not shipped yet, so perhaps I am missing something which will be obvious once I have the physical copy.

Overall, Adventure Anthology: Blood revisits some early Lamentations of the Flame Princess modules with modern art and layout. Even for owners of the original modules, the new art and layout certainly justifies the cost of the PDF. I look forward to receiving my physical copy, which I am sure will be up to LotFP‘s usual excellent standards for physical products. As someone who discovered Lamentations of the Flame Princess after the originals of these modules were already out of print, I am very pleased that these adventures have been made available again in anthology form.